Inserting Life into the Modern Mall

This blog was prepared by the authors (Peter Trio & Robert Ungar) in their own individual capacities. The opinions expressed in this blog are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the Center for Creative Land Recycling, its Board or its staff.

When asked later in life about the thousands of shopping malls he inspired, Victor Gruen – ‘Father of the Shopping Mall’ and ‘Architect of the American Dream’ – had this to say: “I refuse to pay alimony to those bastard developments. They destroyed our cities.”

Modernism was meant to provide a fresh approach to the way in which we design our cities. Free from the constraints of historic precedent, design was no longer an aesthetic, it was function. With Modernism as their new tool, architects now had the ability to shape the life of those living between their walls. Suburbs sold Americans the promise of light, air, and space, but relocating required them to leave behind the community of the urban core. Austrian immigrant and architect Victor Gruen would introduce to America a cure for the social isolation caused by suburbia: the shopping mall. In 1956, the first mall of its kind opened in Southdale, Minnesota, promising community, commerce, and a palette of native California landscape. The idea spread like wildfire. By 1990, thousands of indoor shopping centers had sprouted up across the United States2. Prairies, forests, and wetlands were exchanged for asphalt parking lots and big box department stores. The need for community in suburbia was the bait for consumerism3. For the first time in history, the civic center of town would be under a privately owned roof and thus at the mercy of a capitalist system. The relationship was symbiotic, as the landlords provided a healthy tax base for the region in return for the subsidization of automobile infrastructure.

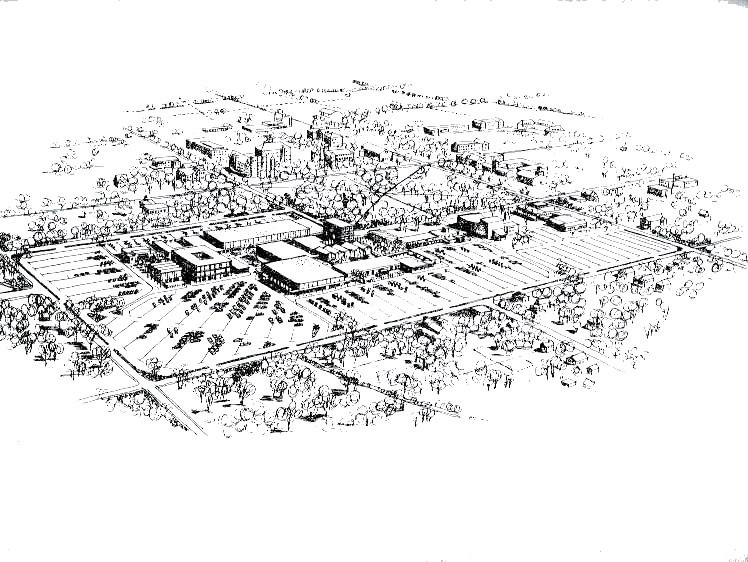

Victor Gruen’s depictions of suburban shopping centers look different than they would eventually play out, with more density and an adjacency to green space and historic core. Oberlin Central District Study by Victor Gruen Associates, page 9 courtesy of Oberlin College Archives, 1975

Shopping malls are not unlike the ecosystems of prairies, forests, and fields that preceded them. Retailers prey on consumers, using flashy colors, bright lights, and perfume to lure their victims in4. In any ecosystem, change is a part of life. In fact, minor disturbances are often critical to the health of many ecosystems (think of the ecological succession that follows a forest fire as life re-establishes itself amidst the ashes). Among other forces, e-commerce (Amazon), alternative transportation (Uber/Lyft/Autonomous Vehicles), and a changing consumer demographic are all obstacles around which shopping centers are currently maneuvering.

While some malls have succumbed to these changes, others have managed to adapt and survive. One example is Santana Row in San Jose, California, which is applying the New Urbanist formula5 of faux-European streets and mixed use paseos. These developments are often considered a high-cost, high-risk endeavor as the formula still depends on retail as the foundation of its success. While understanding the implications of New Urbanism mixed-use is important, it is telling to observe how large retail developments have managed to evolve without the heavy cost of redevelopment or dependency on retail revenue.

Case Study: Central Bus Station, Tel Aviv, Israel

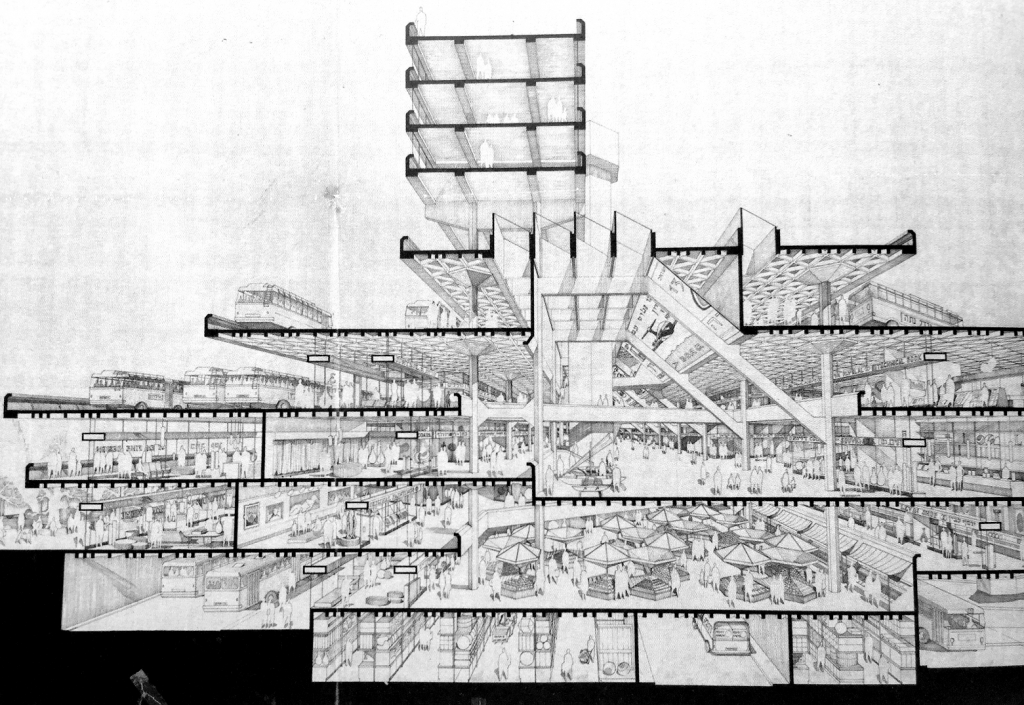

Sectional Perspective of the intended design of Tel-Aviv’s Central Bus Station. Ram Kamari, 1967

The Central Bus Station of Tel-Aviv, Israel was a privately funded mega structure bus terminal/shopping mall. The project was funded under the presumption that it would generate revenue from the 1,400 storefronts within. Thirty years after opening, the building is largely abandoned, dirty and poorly maintained. Despite its initial appearance much life exists. Vacancy in the eight story, windowless concrete monster enabled many marginalized communities to make space to meet their needs. Pushed out of other, more controlled parts of the city, migrant workers’ churches, refugee childrens’ kindergartens, professional training colleges, art studios, a Yiddish book library and a bus tunnel turned bat cave can thrive thanks to lower rents and a lack of surveillance. The space also enabled groups such as ONYA Collective to reclaim vacant spaces for public use with ecological interventions, urban agriculture, art and community organizing. The process started to change minds, slowly impacting the city to support initiatives in the area, and inspiring additional social entrepreneurs in reclaiming the space for healthier public uses. The opportunities to imagine and work towards a future for the neglected space helped mobilize people and impacted the professional trajectories of urban designers, landscape architects and community activists in that part of the world.

To understand the success of the Tel-Aviv Central Bus Station, one must have metrics not found on a pro-forma or business plan. The territory in which this project operates is the gradient between public and private, design and planning.

A project becomes a place when the needs of the community are recognized and realized by public institutions. The private sector can fulfill these needs with appropriate assistance from the public sector. In many urbanizing regions of the world, traditional redevelopment processes generate resistance from NIMBYs (Not In My Backyard). This is often because private developers are not fulfilling the needs of the existing community. A more thoughtful approach would be listening, then allowing a gradual growth of an ecological and social system that could be paired with an adjacent development.

As American malls fail to evolve to meet the needs of the current generation, the local community is often left to deal with aging infrastructure (storm sewers, abandoned big boxes, and services roads) once supported by a healthy retail tax base. In many regions, this can mean increased flooding, urban heat island effects, and decreasing property values. Though a challenge for the community, this is also an opportunity. It is time that cities and the local community come together to identify the needs of their neighbors and begin to envision a future for their malls that goes beyond the nostalgia of the past. These malls can evolve to become areas of suburban wilderness, serving children & families with adventure play. In Germany, an abandoned tarmac was strategically eroded and in a matter of just 10 years a wilderness emerged through its cracks. Recreational fields, bike paths, and parks might be able to better connect the acres of asphalt to the adjacent community. Malls might evolve to provide makerspace, where craftsman can both work and sell their goods. Many of these malls are so large and underutilized that a combination of these functions can emerge overtime as part of an evolution.

It is time to not just envision a future where the mall will survive, but where the mall will thrive. Join us for more as we present a webinar on the topic of inserting life into the modern mall on October 16th at 11am PT/2pm ET.

About the Authors

Peter Trio spent his childhood on the farms, woods, and lakes of Minnesota. His professional experience is in green infrastructure, architectural detailing, and landscape design throughout the Midwest and California. Peter is the founder of The Thirdscape Initiative, which is focused on the evolution of our suburban landscapes to ensure they are socially productive, economically sustainable, and ecologically resilient. Currently Peter is a landscape designer at the firm WRT in San Francisco.

Robert Ungar is an Oakland-based, Israel-raised architect and urban designer. He currently works on urban design projects, in parallel to researching adaptation of cities to climate change in San Francisco. He co-founded the Tel Aviv-based ONYA collective, an interdisciplinary group developing innovative urban interventions and runs community and art events in the field of urban ecology. He facilitated “Next Station”, a cross-sector initiative to transform abandoned areas of Tel-Aviv’s Central Bus Station, a massive shopping mall and transit center, into active, green spaces that serve residents and spur bottom-up culture.

______________________________

1. Hardwick, M. Jeffrey, and Victor Gruen. Mall Maker : Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, ©2004

2. Dunham-Jones, Ellen, and June Williamson. Retrofitting Suburbia : Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs. Hoboken, N.J. : Wiley, ©2011

3. Hardwick, M. Jeffrey, and Victor Gruen. Mall Maker : Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, ©2004

4. Chung, Chuihua Judy, Jeffrey Inaba, Rem Koolhaas, and Sze Tsung Leong. Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. Project on the City: 2. Köln : Taschen ; Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard Design School, 2001., 2001

5. Tachieva, Galina. Sprawl Repair Manual. Island Press, 2010.